H. Em. Rabbi Dr Eliyahu ben Abraham

Yshevat Esnoga Beth El. ©

Nomos

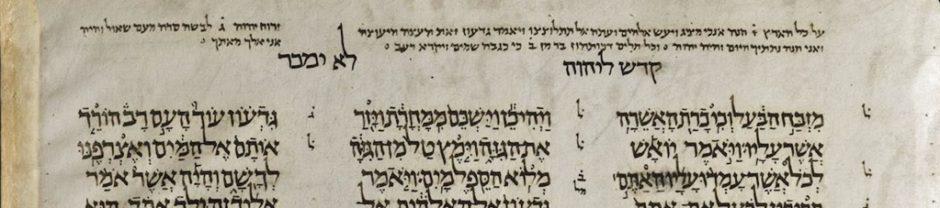

Hakham Shaul makes his first use of the Greek word “nomos” in Romans 2:12. Therefore, we need to discuss the implications of Hakham Shaul’s use of the word and its meaning. Without elaborating at length, the true meaning of “nomos” from a lexical perspective, “nomos” is defined as the equivalent to the Hebrew word “Torah.” The translators of the Septuagint (LXX) when translating the Torah (specifically the five books of Torah) translated the Hebrew word Torah as “nomos” 200 out of the 220 times that it is found in the Pentateuch.[1] Hakham Shaul uses “nomos” in a number of ways in his Igeret to the Romans. However, what we must understand and bear in the forefront of our minds is that Hakham Shaul used the Greek word like the translators of the LXX. Therefore, Hakham Shaul’s “nomos” is Torah essentially.

Bruce points out that Hakham Shaul uses “nomos” in four ways.

- The Law of G-d

- Torah specifically the Pentateuch

- The “Tanakh”

- The Oral Torah

- Principle[2]

Missing from Bruce’s explanations are other meanings of the Hebrew word “Torah.” For example, Torah also means…

- Instruction

- Directive

- Mitzvah

- Choq (supra-rational laws)

- Mishpat (judgments, specifically from a Bet Din)

- Halakhah

- Divine teachings, revelation of the Divine will

- Prophetic moral exhortations

- Rule

- Guide

We cannot read this list as being exhaustive. The concept of “Torah” is by far more far reaching that any simple definition.

The complexity of Hakham Shaul’s use of “nomos” relates to the allegorical meanings associated with the Torah. In his Igeret (letter) to the Romans Hakham Shaul is dealing with practical situations[3] and therefore the Nazarean Codicil and the present Igeret is the record of Nazarean halakhah. However, Hakham Shaul is showing us that the Nomos/Torah is so cosmic that G-d judges the Gentiles, who are without excuse according to the cosmic truth of the Torah.

Therefore, we must deduce that the Oral Torah/Nomos is the fabric of the cosmos. Consequently, we inhabit a nomos – a normative universe. We constantly create and maintain a world of right and wrong, of lawful and unlawful, of valid and void.[4] We must further understand that the cosmos of dialogical narrative and rhetoric. Thus, we will see the cosmos as a “nomos narrative.” Some have referred to this as a sacred canopy.[5]

The “normative” universe is held together by the power (force authority) of its interpretative agents known as Sages/Hakhamim (men of wisdom) in relation to the nomos/Torah of the cosmos. Through the interpretive hermeneutics of the Sages, we enter the domain world of Torah observance. The Torah in and of itself is a nomos narrative. While it contains 613 mitzvoth, it reveals them only through narrative rhetoric. Consequently, the pattern of Law (nomos) and “Law giving” is given primarily in rhetoric and narrative.

This brings us to the age-old question of why the Torah begins with B’resheet (Gen.) 1:1 instead of Shemot (Ex.) 12:2. The general deduction is that G-d wanted to show Himself as the creator and therefore just in giving Eretz Yisrael to the Jewish people rather than the nations.[6] Allegorically, G-d wants to reveal to us that the cosmos is a Divine nomos narrative, the Divine story of His eternal benevolence. Furthermore, we can derive from the written Torah a pattern of nomos rhetoric. The nomos narrative is a halakhic “story” being told through the medium of time. We must also note that G-d gave us the “613 mitzvoth” through the medium of a specific nomos narrative (“I G-d brought you out of Egypt”). The narrative established grounds for G-d’s mitzvoth and halakhah. Therefore, the covenantal nomos is given in legal rhetoric because this is the true essence of the cosmos. It is for this reason that scientists refer to principles of the cosmos as the “laws of nature” i.e. nomos phuseos, lex naturalis. What is important for us to derive from this is that G-d’s law (nomos/Torah) is always couched in narrative form it cannot be wrenched from this rhetorical medium. Likewise, when we read nearly all legal documents they are joined to a narrative rhetoric. All courts of law depend on narrative and rhetoric as a means of legal decision-making.[7] Therefore, we cannot separate law/nomos/Torah from narrative form.

On another level, the Torah naturally equates itself to a cosmic nomos narrative. In other words, the Torah depicts the cosmos as a nomos narrative showing G-d’s cosmic authority. B’resheet (Genesis) shows the origins of the Cosmos through G-d’s verbal command – nomos. These verbal commands form a nomos narrative and history of the chief events of creation. As we further read in B’resheet, we see the narrative of nomos unfold in a very logical way. The Order of the Torah narrative is for the sake of understanding among other things, the communal interaction of humankind. Therefore, halakhah, mitzvoth as a nomos narrative teach humankind how to interact socially.

Nazarean Codicil

This pattern helps us to have a better understanding of the narrative structure of the Nazarean Codicil as a “nomos narrative.” By presenting the nomos in a narrative, we can now approach the Nazarean Codicil as nomos rhetoric. Furthermore, we can now see how Hakham Shaul can present a nomos narrative in Igeret (letter) form to both Jews and Gentiles in Rome. The Romans, Jewish and Gentile congregation would easily note that the Igeret was a legal document with numerous legal norms. The idea of a cosmos as “nomos narrative” would have been apparent to a Greco-Roman audience.[8]

The Nazarean Codicil naturally falls into Six Orders.

- Peshat – School of Hakham Tsefet – Mark, 1 & 2 Peter, Jude

- Tosefta – Additions by Hakham Shaul – Luke

- Remes – Hakham Shaul’s school of Allegory All the Pauline Epistles & James

- Darash – Midrashic Teachings of Hakham Matityahu – Matthew

- So’od – Hakham Yochanan’s school of So’od – John & all his Epistles

- Festival and Fast – Ritual Hermeneutics

While these patterns need further research, and possible redefinition we can see that they fall in to specific narrative categories. In this manner, we see that the patterns are very similar to the way that the Oral Torah is divided. However, the Nazarean Codicil mirrors the “nomos narrative” of the Tanakh much more closely. Yet, the way that the Nazarean Codicil mirrors its Biblical Narrative in its Torah Seder is closer to Midrashic and So’odic narratives of the Oral Torah.

Like the “nomos narrative” of the Torah, the Nazarean Codicil projects its rhetoric in communal judgments and declarations. These judgments and declarations establish nomos – laws for social interaction and discourse. Thus we can see that Hakham Shaul sends an Igeret to the Romans outlining the “nomos” – law for Gentiles who are “turning towards G-d.”[9] Note the legal vocabulary of the initial part of Hakham Shaul’s address.

Through him (Messiah), I have received chesed[10] and an Igeret Reshut[11] to bring Messiah’s authority[12] over all the Gentiles turning to God,[13]

Of course, this brings in a new factor of Messiah and Nomos/Torah/Law, which is a critical element to the “Nomos Narrative.” From this, we drive the idea that the nomos narrative has a teleology in mind. The nomos narrative of the Torah and Nazarean Codicil both project a very specific teleology as a goal to be achieved on a cosmic level. The Nomian teleology is a legal description of the times we will experience such as the Y’mot HaMashiach and the Olam HaBa wherein the communities therein will live by the teleology of the nomos narrative we seek to express at present. Therefore, the nomos narrative of the cosmos (Oral Torah) is the “Nomos of Tikun” in this we understand “Tikun” to mean rectification or more properly “return.” Therefore, the cosmic “nomos narrative” outlines the path between the Olam HaZeh and the Olam HaBa.

From the Nazarean Codicil and its “order” in hermeneutic headings we come to understand the nomos narrative of the cosmos to be defined through exegetical hermeneutic exercises mastered by the Hakhamim. It is for this reason that we must have Hakhamim (Torah Scholars) to interpret the overarching nomos narrative of the Oral Torah a “Higher Law: Living Nomos.”[14]

The Order and Pattern of the Oral Torah and its Narrative

As we have seen above, the Nazarean Codicil follows a specific pattern in its re-narration of the Oral and Written Torah (Nomos). Fraade outlines the Oral Torah in the following words.

The pattern that we saw in second temple Jewish literature-of reconstituting biblical laws by extracting them from their biblical narrative contexts so as to topically gather and rearrange them-is carried very much further in the Mishnah (commonly attributed to R. Judah the Patriarch of the early third century), than in any of its antecedents. There, biblical and post-biblical laws are combined and organized according to topical, non-biblical rubrics: six orders, divided into sixty-three tractates, subdivided into 523 chapters, into which individual Mishnaic rulings are arranged. But to conceive of this simply as an ideologically innocent editorial reordering would be a gross simplification, since the Mishnah fundamentally transforms received laws according to its own Mishnaic language, oral syntax, and dialogical rhetoric.[15]

Samely presents a more exhaustive investigation of “Rabbinic Interpretation of Scripture in the Mishnah.”[16] Nevertheless, we see that Torah/Nomos is never divorced from a narrative form. The Oral Torah, a higher “living Torah,” like the Nazarean Codicil categorizes its narrative into specific genre for the sake of specifics.

When the Sages of the second Temple period reconstituted “biblical law,” they understood that nomos rhetoric could not be divorced from that form. Writers like Josephus and Philo were aware of the same truth. Josephus gives a very vague view of the mitzvoth and the halakhah. Philo looks at the mitzvoth and halakhot in very much the same way that the Talmud does. Likewise, Philo sees the nomos as a cosmic narrative. As such, Philo show us the application of re-narration of nomos in allegorical form. Consequently, we should be able to see some sorts of parallel between Hakham Shaul and Philo. Hakham Shaul’s allegorical Igeret to the Romans viewed the Gentiles in a negative light. Philo has almost the exact same view.

Abraham 135 As men, being unable to bear discreetly a satiety of these things, get restive like cattle, and become stiff-necked, and discard the laws of nature, (τῆς φύσεως νόμον) pursuing a great and intemperate indulgence of gluttony, and drinking, and unlawful (ἐκθέσμους) connections; for not only did they go mad after women, and defile the marriage bed of others, but also those who were men lusted after one another, doing unseemly things, and not regarding or respecting their common nature, and though eager for children, they were convicted by having only an abortive offspring; but the conviction produced no advantage, since they were overcome by violent desire; (136) and so, by degrees, the men became accustomed to be treated like women, and in this way engendered among themselves the disease of females, and intolerable evil; for they not only, as to effeminacy and delicacy, became like women in their persons, but they made also their souls most ignoble, corrupting in this way the whole race of man, as far as depended on them. At all events, if the Greeks and barbarians were to have agreed together, and to have adopted the commerce of the citizens of this city, their cities one after another would have become desolate, as if they had been emptied by a pestilence.[17]

Fraade sums Philo’s nomos narrative as follows.

Philo’s extraction and reordering of the biblical laws serves much more than simply a need to render them more accessible or applicable. Through his allegorizing interpretations of the laws, Philo effectively removes them from the “horizontal” narrative of biblical history and repositions them within an overarching “vertical” narrative of the individual soul’s perfection and ultimate ascension to reunion with its divine, heavenly source, which similarly pervades his allegorical interpretations of the biblical narratives and personalities.[18]

Implicit in Philo’s writing and in conjunction with Hakham Shaul is the idea that the nomos is comic. Furthermore, Philo shows us exactly why Hakham Shaul uses Abraham as the model for his interaction with the Gentiles.

Abraham 1:276 Such is the life of the first author and founder of our nation (Abraham); a man according to the law, as some persons think, but, as my argument has shown, one who is himself the unwritten law (Torah/Nomos) and justice of God. [19]

The Greek sentence actually sees Abraham as a νόμιμος βίος (Nomimos Bios = Living Torah) αὐτὸς ὢν καὶ θεσμὸς ἄγραφος (who is himself the unwritten law).[20] Hakham Shaul’s words in the present pericope now become evident. As such, Abraham became a “living Torah/Nomimos Bios” of the unwritten law i.e. the Oral Torah or Torah of the cosmos. Here we find some similarities in the So’odic narrative of Yochanan 1:14 and the logos (nomos) became “flesh” i.e. a living Torah. Therefore, Abraham’s descendants[21] are required to keep the Oral Torah, the higher, “living Torah.”

Did Abraham know the Oral Torah or the Written Torah? During the time of Abraham, the Torah was only in Oral form. In chapter four of the Igeret to the Romans, Hakham Shaul will bring Abraham to make a point concerning his halakhic norms. Yet, here we see that Abraham is a prototype for Gentiles to follow. Hakham Shaul shows that the Gentiles have the Oral Torah, cosmic nomos narrative in their conscience. As such they are guilty of violating the Oral Torah when they “sin.”

From Abraham we learn

- The cosmos is a living Nomos/Torah

- The Nomos/Torah resides in the conscience of humankind (Jews and Gentiles)

- Abraham embraces the Nomos/Torah of the Cosmos and became a “Nomimos Bios” (living embodiment of the Oral Torah) in the same way that Yeshua did

B’resheet (Gen) 14:18-19 And Melchizedek king of Salem brought out bread and wine; now he was a priest of God Most High. He blessed him and said, “Blessed be Abram of God Most High, Creator of the heavens and earth.”

Allegorically this passage tells us that Abraham attended the Yeshiva of Shem (Melchizedek) and completed his studies there. How so? Bread can be seen as an allegory for halakhah and wine is the haggadic portions of the Oral Torah. How can we determine that he completed these courses? Melchizedek king of Salem, “shalam” is that which is completed and whole.

We hope that we have learned from this lesson that the Torah/nomos is a living Torah, personified in Messiah. However, Messiah is typical of those like Abraham who made their lives a living Torah learned and discerned from the Torah/nomos of the Cosmos, i.e. the Oral Torah that serves to instruct humankind in the path that G-d as the creator has laid out for humankind. Hakham Shaul’s appeal to the conscience of the Gentile is an allusion to the truth that the Oral Torah is cosmic in nature and therefore the Oral Torah and their faithfulness judge all men therein. The “lawless” are in fact those who do not exercise self-control and are guilty and punishable for crimes against the Torah.

The Torah must be given in a narrative form. The narrative form is faithfully followed in the Tanakh. The Nazarean Codicil closely mimics the pattern of the written and Oral Torah. The Nazarean Codicil; re-narrates the Torah in Messianic, halakhic form. The Oral Torah now in written volumes follows a very similar approach to halakhic/nomos of the Nazarean Codicil.

[1] Fraade, Steven D. (2005) “Nomos and Narrative Before Nomos and Narrative,” Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities: Vol. 17: Iss. 1,Article 5. p. 4 Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjlh/vol17/iss1/5

Fraade also points out that the noun “Torah,” means “directive,” and other words may have seemed proper but the translators of the LXX were consistent in translating Torah as Nomos.

[2] Bruce, F. F. The Epistle of Paul to the Romans: An Introduction and Commentary. The Tyndale New Testament Commentaries 6. Leicester, England : Grand Rapids, Mich: Inter-Varsity Press ; W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co, 1983. pp. 52-53

[3] Tomson, Peter J. Paul and the Jewish Law: Halakha in the Letters of the Apostle to the Gentiles. Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum Ad Novum Testamentum, v. 1. Assen [Netherlands] : Minneapolis: Van Gorcum ; Fortress Press, 1990. p.55 Note: this is our interpretation of Tomson’s words

[4] Cover, Robert M., “The Supreme Court, 1982 Term — Foreword: Nomos and Narrative” (1983). Faculty Scholarship Series. Paper 2705. p. 4

[5] Berger, Peter L. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. Reprint edition. New York: Anchor, 1990.

[6] Cf. Rashi’s comments to Gen. 1:1

[7] Tractate Sanhedrin demonstrates this clearly in showing us how the Judges are taught how to interact with “witnesses” in order to extract nomos from their testimonies.

[8] Greene, Moira 17, 36; W. K. C. Guthrie, History of Greek Philosophy. Vol. III (Cambridge: The University Press 1962–1981) p. 55. and Martens, John W. One God, One Law: Philo of Alexandria on the Mosaic and Greco-Roman Law. Ancient Mediterranean and Medieval Texts and Contexts, v. 2. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2003 ch.1

[9] 2 Luqas 15:19-21 Therefore, my judgment is that we should not cause difficulty for those from among the Gentiles who turn to God, but we should write a letter to them to abstain from the pollution of idols and from sexual immorality and from what has been strangled and from blood. For [the rest you have] Moshe who has those proclaiming him in every city from ancient generations, because he is read aloud in the synagogues on every Sabbath.”

[10] Chesed: It is G-d’s loving-kindness, to bring Gentiles into faithful obedience of the Torah and Oral Torah through the agent of Yeshua our Messiah.

[11] Igeret Reshut: “Letter of Permission.” The Bet Din of Yeshua’s three pillars, Hakham Tsefet, Hakham Ya’aqob and Hakham Yochanan, would have issued this Igeret Reshut. This would have been very important to the Jewish Synagogues of the first century. Furthermore, we can see that Hakham Shaul must have followed this practice in all of his interactions with Jewish Synagogues. In the second Igeret to Corinthians Hakham Shaul asks if he needs an Igeret Reshut. Cf. 2 Co 3:1. Hakham Shaul’s Igeret Reshut is his letter of acceptance as a Chaber among the “Apostles.” His office is subjected to the Three Pillars rather than the Bat Kol. We find b. B.M. 59b as a precedent for understanding that a Bat Kol does not usurp the authority of the Bet Din. In this case, the Bet Din are the chief Nazarean Hakhamim.

[12] Name: ὄνομα – onoma, (name) meaning authority

[13] Romans 1:5

[14] Martens, John W. One God, One Law: Philo of Alexandria on the Mosaic and Greco-Roman Law. Ancient Mediterranean and Medieval Texts and Contexts, v. 2. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2003 ch. 3

[15] Fraade, Steven D. (2005) “Nomos and Narrative Before Nomos and Narrative,” Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities: Vol. 17: Iss. 1,Article 5. Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjlh/vol17/iss1/5

[16] Samely, Alexander. Rabbinic Interpretation of Scripture in the Mishnah. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. pp. 1-110

[17] Philo, o. A., & Yonge, C. D. (1996, c1993). The works of Philo: Complete and unabridged (422). Peabody: Hendrickson.

[18] Fraade, Steven D. (2005) “Nomos and Narrative Before Nomos and Narrative,” Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities: Vol. 17: Iss. 1,Article 5. Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjlh/vol17/iss1/5

[19] Philo, o. A., & Yonge, C. D. (1996, c1993). The works of Philo: Complete and unabridged (422). Peabody: Hendrickson.

[20]Kittel, Gerhard, Geoffrey William Bromiley, and Gerhard Friedrich. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1964. 4:1052.

[21] Abraham descendants refer to the Jewish people who have both forms of the Torah and the Gentiles who are held accountable to the Oral Torah.