Yeshua’s relation to the “Oral Torah” is a place from much discussion. Scholars are ever making new discoveries in this field. This is because scholars are beginning to take a new approach to the Oral Torah and the Gospels. That approach is the investigation of the oral transmission of rabbinic materials. Because of contiguity, scholars relate the Nazarean Codicil to the Oral Torah, beginning to apply the hermeneutic principles of oral transmission to the Nazarean Codicil are making new discoveries.

Transmission of Yeshua’s Mesorah

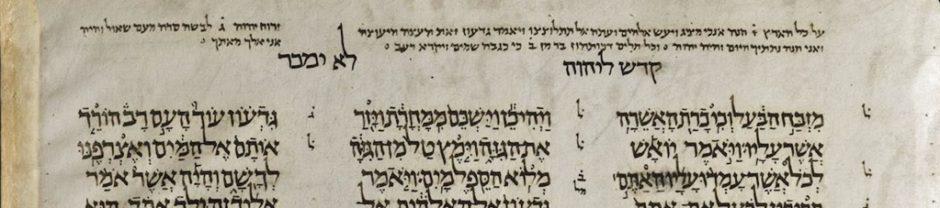

Unfortunately, the present generation has a great deal of difficulty understanding the art of orally transmitted materials. This applies to scholarship as well as laity. With the advent of the printing press, invented around 1440, humanity has allowed the mechanism of memory to wane. The ability to memorize texts, lectures and orally transmitted materials is more a lost art than modern practice. Furthermore, the truth of orally transmitted texts does not even dawn on the modern audience. Because we are so “book” oriented, we do not understand the dynamics of oral transmission, memorial apperception,[1] auditory reception, and the interfacing of memory and manuscript. Many people today are better suited to auditory learning. These people may have aptitudes, which are best suited for memorizing orally transmitted materials. Others have eidetic memory. This is not to say that they have photographic memories. This simply means they are better suited to visual learning. While we tend to think of the idea of reading accompanied with the ability to write, this was not necessarily how things worked in the first-century. Many people had the ability to read. However, the ability to write, especially on the level of a scribe, was not given to the common person. Those who possessed scribal skills were better trained in the art of writing than the average person was.[2] However, we must assert that the father of the Jewish child (boy) was specifically given the task of educating his son in the Torah. This did not necessarily mean teaching ones son to read and write. Nevertheless, we know that many fathers took it upon themselves to provide for their sons the ability to read and write. While those skills may not have been on the level of the Sofer, we must believe that the Jewish boys in the first century were fully capable of reading and writing. The elementary school (bet seper), in which the young Jewish boy was taught to read the Torah with correct vocalization, accent, and fluency also taught him to be able to effect relatively simple Aramaic translation of the (targum). While the Targum was in Aramaic, the lingua franca was Mishnaic Hebrew. The venue of languages spoken included Biblical Hebrew, Mishnaic Hebrew, Greek[3] and Aramaic. Aramaic served as a scholastic language whereby they studied the Targum to the Torah. However, Mishnaic Hebrew was most likely the lingua franca.

In searching out the oral transmission of the tradition (Mesorah) of Yeshua, we must not forget that Yeshua selected some of the most astute men of his day as talmidim. While I realize that many of the early church fathers and form critics wanted to relegate to them illiteracy and simplicity,[4] these talmidim were very astute.

Because Yeshua himself was most likely trained as a “tanna”[i] and a “sofer” we might surmise that his talmidim were very similar in talent and skill. Some of Yeshua’s talmidim may have been a closely-knit group of talmidim before they encountered Yeshua. Yeshua’s selection of talmidim in Mark and Luke give a striking picture of their possible connection.[5] The footnoted passages give some evidence to the possible connection between the four men, which may have existed before their selection as Yeshua’s talmidim. While they may have only been μέτοχος metochos {met’-okh-os} fishing or business “partners,” it is also possible that they formed a chaverim.[6] For example, Martin Hengel[7] notes that the talmidim may have been more than acquaintances before they became the talmidim of Yeshua. It seems logical that these men, from the same region attended the same Synagogue and most likely learned from the same Hakham or Rabbi[8]. Here I would purport the idea that they attended a Synagogue near Kafarnaum (Capernaum) while Yeshua, rabbinically trained by Shimon b. Hillel lived in Tzfat, which overlooked the Kafarnaum community. Therefore, the talmidim of Yeshua already had graduated elementary school (bet seper), in which they were taught to read the Torah with correct vocalization, rhythm, and fluency. The “tradition of the Fathers,” particularly of the P’rushim, was learned in the Jewish homes, synagogues, and courts, but above all it was handed down (mesorah) by learned specialists in the bet hamidrash (“house of study,” an advanced school). The Synagogue of Kafarnaum may have had such a specialist. Given our understanding of the Kallah secessions and the genuine purpose of the Sanhedrin it is probable that a level of education beyond the elementary bet seper existed where Hakham Tsefet and his collogues could have obtained a level of education above the elementary stage. Without stretching the realm of the possible any of these talmidim may have served on a Bet Din.

Because the “tanna” could memorize large sums of materials, the talmidim must have been near tannaim with similar capabilities. I attribute Hakham Tsefet with these skills, being the authority of Yeshua’s talmidim. I would also further the idea that Hakham Tsefet was a halakhic genius as well. While the Nazarean Codicil has somewhat of a Mishnaic structure, we see that the “Petrine School” formed the catechistic foundations for all the believers of Yeshua. Some scholars have noted Hakham Tsefet’s poetic and liturgical abilities.[9]

“Q”

Scholars of the form criticism schools suggest that Q — Quelle (source), was the basis for the “synoptic gospels.” The theory is that the synoptic Gospels were derived from two sources. The first being Mark and the second being “Q.” The “Q” question that everyone has the greatest difficulty with is, which came first Mark of “Q?” In addressing the “synoptic problem,” the discussion is how to resolve the seeming conflict between the three gospels Mark, Matthew and Luke, albeit this is an over simplification of the “problem.” In their ignorance, scholars reached an impasse with this “synoptic problem.” The cause for their impasse is their failure to consider the hermeneutics of the Rabbis from the first century and before. The four leveled system referred to as PRDS has been overlooked while they search for the “needle in the haystack.” The PRDS hermeneutic, when correctly applied alongside the triennial Torah reading schedule solves all the problems previously considered insurmountable. However, they have exhausted their minds and sources trying to find Q. They have inquired as to whether Q was an oral tradition passed down from some unknown source. And, they have conjectured that Q was some document now lost that Matthew and Luke used to create their accounts of Yeshua’s life. Again, this is an oversimplification of the problem.

A major problem with the form critical analysis of the Nazarean Codicil is chronology. While there may be a smattering of chronology in the gospels, the intent is not chronological. The intent is to match the life of Yeshua with the triennial Torah reading cycles. When the life of Yeshua is divorced from this context, truth is impossible. I am certain scholars of the critical school will continue to try to force Yeshua into their mold and the search for the historical Yeshua will continue to be fruitless. We maintain that the “gospels” were not written for the sake of presenting a “historical Jesus.” The purpose of the ‘Gospels” was to identify Yeshua as the “living embodiment of the Torah.” The mechanism they used to illuminate his life was as we have already stated the triennial Torah reading cycle.

My answer to the Q question is simple albeit thesis. Q was Hakham Tsefet! Hakham Tsefet was the walking talking tradition (mesorah) of Yeshua our master. One problem that the form critics could never solve is the problem of which came first Mark or Q. If Q turned out to be the person Hakham Tsefet, they would find their answer. The answer to the Q question is the Petrine School, which every gospel writer attended.

The mechanics of oral transmission point to specific language and homiletic structure. This structure demands the teacher speak, using strong mnemonic utilities. The poetic nature of Mishnaic Hebrew allows the teacher to speak in alliteration, assonance, rhythms and rhyme.[10] Cantillation, repetitious sounding vowels and the rhythmic nature of Mishnaic Hebrew would have made the sayings of Yeshua more readily available to the trained mind of a person with “tanna” like skills. Scholars reading the Lukan[11] account of Yeshua’s address in the Synagogue suggest the possibility of Yeshua serving as a Ḥazon or Sheliach Tzibbur.[12] In the advent, that the “Darshan” speaker was not able to speak in the dialect of the congregants a “meturgeman” (translator) was always present. This demonstrates Yeshua as a master of language and liturgy. Therefore, Yeshua’s use and command of language allows him to transmit his “Mesorah” in a very convinced manner. While the main system for learning Yeshua’s Mesorah and all rabbinic teachings was primarily oral, we must assert that there was a possibility of writing as noted above. Because Hakham Tsefet is the most authoritative talmid, we might conjecture that he may have taken notes from time to time to help with recall. Not to beat the dead horse, but herein lays Q. This does not negate the possibility of all Yeshua’s talmidim being able to read, write and take notes on any given lecture.

In considering the Petrine School, we would better understand each of the “gospels” if we realized that the materials were orally transmitted. In dealing with Mark, for example we know that Hakham Tsefet is the real author behind the sofer. Hakham Tsefet orally dictated materials, which Mark was to write down. While we imagine an author dictating his materials to a secretary, nothing could be farther from the truth. In the case of Hakham Tsefet and his scribe, we would imagine that Hakham Tsefet dictated the orally memorized materials dictated to him by Yeshua. Mark in turn wrote what Hakham Tsefet recited to him. There existed here a methodical, controlled transmission of teachings of Yeshua, which likewise insured the careful handing down of those teachings. We might conclude that the methodological system was synonymous with the rabbinic system of transmitting the oral torah. Like the rabbinic system, the mesorah of Yeshua would have consisted of short terse statements designed to aid memorization and transmission. The mechanism of “pars pros toto,” used as an aide-mémoire mechanism for connecting Yeshua’s mesorah with the Torah facilitated exhaustive recall. However, we can see that the Talmud promotes a system whereby the memorization and retention of an effective system of mesorah memorization. Yeshua’s talmidim most likely utilized this same system to transmit his mesorah.

- Eruv 54b Our Rabbis learned: What was the procedure of the instruction in the oral law? Moses learned from the mouth of the Omnipotent. Then Aaron entered and Moses taught him his lesson. Aaron then moved aside and sat down on Moses left. Thereupon Aaron’s sons entered and Moses taught them their lesson. His sons then moved aside, Eleazar taking his seat on Moses right and Ithamar on Aaron’s left. R. Judah stated: Aaron was always on Moses right. Thereupon the elders entered and Moses taught them their lesson, and when the elders moved aside all the people entered and Moses taught them their lesson. It thus followed that Aaron heard the lesson four times, his sons heard it three times, the elders twice and all the people once. At this stage Moses departed and Aaron taught them his lesson. Then Aaron departed and his sons taught them their lesson. His sons then departed and the elders taught them their lesson. It thus followed that everybody heard the lesson four times. From here R. Eliezer inferred: It is a man’s duty to teach his pupil [his lesson] four times. For this is arrived at a minori ad majus: Aaron who learned from Moses who had it from the Omnipotent had to learn his lesson four times how much more so an ordinary pupil who learns from an ordinary teacher.

The fourfold repetition of materials and lessons facilitated prolonged memory.

Anyone who has lectured before an audience understands the orally transmitted process. In the preparation of the lecture, the orator rehearses the materials until he or she has developed a fluid path for the presented materials to follow. The Yelammedenu homily of the first century was crafted in a way, which expedited memorization and recollection. However, one difficulty that exists in the process of recording orally transmitted materials is the change of medium.[13] Dictated materials change form when they are printed. Frequently, there is evidence of this process in written materials. In the case of Mark (Petrine School), we can easily see evidence of this process.

Here I will not give lengthy exhibits of this process, because others have written on this process. However, I will give brief examples.

“Take courage; it is I, do not be afraid.”[14]

This example written in English cannot show the rhythm and rhyme of the Mishnaic Hebrew, behind the translation. Nonetheless, this small terse statement is easily memorized. Not only is it easily memorized, when the simple statement is recalled, the whole events surrounding the statement come to mind.

The materials referred to as the “beatitudes” are another terse example.

Blessed are the peacemakers, For they shall be called sons of God[15]

Again, the rhythm and fluidity of Mishnaic Hebrew do not reveal themselves, yet the statement, even in English, would not be hard to memorize. Furthermore, the subject of the whole homily is readily memorized when broken down the materials in manageable pieces.

[1] The mental process by which a person makes sense of an idea by assimilating it to the body of ideas he or she already possesses.

[2] Wansbrough, H. (2004). Jesus and the oral Gospel tradition (reprint T&T Clark academic paperbacks ed., Vol. 64 of Journal for the study of the New Testament: Supplement series). (H. Wansbrough, Ed.) Continuum International Publishing Group. p.160

[3] While Koine Greek was the lingua franca, Classic Greek was the language of the LXX. In my mention of Koine and Classic Greek, I must maintain that neither the LXX nor the Nazarean Codicil will fit into the lingua proper. This is because the language of the LXX and the Nazarean Codicil, inundated with Hebraic aphorisms are not Classical or Koine Greek.

[4] Hooker, M. D. (1991). Black’s New Testament Commentaries: The Gospel According to Saint Mark. London: A & C Black Publishers Ltd. p 2

[5] Cf. Mark 1:16ff; 13:3 cf. Luke 5:7

[6] Cf. m. Toh. 7:4 Some debate seems to surround the issue of Pharisaic “chaverim.” There are those who do not believe that the P’rushim actually formed select groups and isolated themselves from the “am haeretz.” For a deeper discussion see Catherine Hezser, (2007) The social structure of the rabbinic movement in Roman Palestine, Mohr Siebeck, p. 74ff

[7] Martin Hengel (2006 ). Saint Peter, the Underestimated Apostle,. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

[8] Here I use “Rabbi” with the understanding that the formal title “Rabbi” may have come into use near or slightly after the didaction of the Nazarean Codicil.

[9] W. J. van Bekkum, The Hebrew Grammatical Tradition in the Exegesis of Rashi? (See Peter’s Yahrzeit – http://ffoz.org/blogs/2009/12/the_ninth_of_tevet_simon_peter.html)

[10] Edwards, J. R. (2005). Is Jesus the only Savior? Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 59

[11] Cf. Luke 4:16ff

[12] Edersheim, A. (1993). The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. Peabody : Henderson Publishers. p. 303

[13] Kelber, W. (1983). The oral and the written Gospel: the hermeneutics of speaking and writing in the synoptic tradition, Mark, Paul, and Q. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. p. 44

[14] Cf. Mark 6:50

[15] Cf. Mat 5:9

[i] TANNA, TANNAIM, the sages from the period of Hillel to the compilation of the Mishnah, i.e., the first and second centuries C.E. The word tanna (from Aramaic teni, “to hand down orally,” “study,” “teach”) generally designates a teacher either mentioned in the Mishnah or of Mishnaic times (Ber. 2a). Encyclopedia Judaica, Second Edition, Keter Publishing House Ltd Volume 19 p. 505

Schiffman defines “tanna,” as being derived from the Aramaic mean one who has memorized and recited the traditions of the forefathers. Schiffman, L. H. (1991). From Text to Tradition, A History of Second Temple & Rabbinic Judaism,. Ktav Publishing House, Inc. p. 179